At what age does one stop reading bedtime stories to one’s children? Eight? 11?

Perhaps the right answer should be “when the child is ready to stop”. I’m grateful we’re not quite there yet.

A study commissioned by personalised book company Wonderbly found the average parent reads their children bedtime stories until the age of eight, but 10% keep up the tradition beyond 13 or even older.

Daughter is 14, and I’m happy to continue our nightly ritual until she tells me she’d prefer to read alone. It’s quality “us time” at the end of the day, and I feel privileged she still values it.

It’s also one of the rare times I get to read, given my daily juggle as a busy mum, partner and employee. For this reason, I enjoy choosing our reading material as much as Daughter does.

We have moved on as she’s got older; while we occasionally indulge in a Famous Five – partly “for old times’ sake” but mostly because we are both completists with only a couple left to go for a full set – we have also tackled The Hunger Games Trilogy and, most recently, Pride and Prejudice.

I knew the latter well from small and silver screen, but it was my first time exploring Austen’s written word. I was surprised to discover just how pacy it was, and how each short chapter contained an exchange I remembered, suggesting the versions I’d seen were faithful.

We’ve also slogged successfully through Wuthering Heights, and I’d been eyeing up Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier for some time, confident Daughter would enjoy as much as I did this marvellous Gothic drama from the pen of a Cornish literary titan.

I found it utterly thrilling the first time I read it. Until that point, I’d placed du Maurier with Georgette Heyer and Catherine Cookson in a catch-all category of “historical romance” – soft, comfortable, with a watercolour of an attractive couple on the cover.

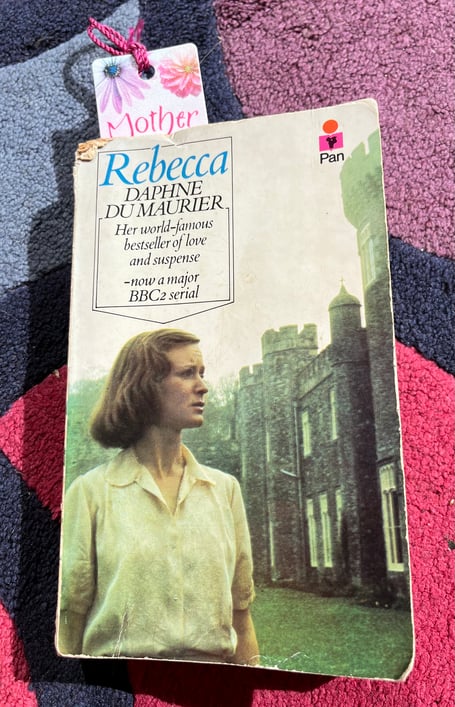

How wrong I was. For starters, my second-hand copy dates back to the late ‘70s and features a still from a BBC drama adaptation starring Caerhays Castle as Manderley.

And what fabulous characterisation: from the mousy narrator, catapulted into marriage and status and well out of her social depth; and the malevolent, Machiavellian masterpiece that is housekeeper Mrs Danvers, as towering a figure as any Dickensian protagonist.

Then there’s the heart-stopping plot twist (no spoilers), revealed midway by a page turn in my Pan paperback.

Second time around, I appreciate the beautiful nuance of du Maurier’s writing. The first two chapters barely touch upon past events, speaking instead from a present that suggests an unhappy exile for reasons yet to be divulged.

It made me long to go back to school and write A-level essays with an enthusiasm I don’t recall from when I was actually there. (I still bristle when recalling The French Lieutenant’s Woman by John Fowles, with its chapter claiming the author has no control over his characters or insight into how they think).

Sadly, come bedtime, I knew I was onto a sticky wicket almost immediately. As the narrator regards her Mediterranean surroundings while longing wistfully (and at length) for autumnal Manderley in soggy Cornwall, I sensed Daughter’s impatience to crack on with the action.

“Do we ever find out her name?” she asked. In answer, I pointed to the picture caption describing actress Joanna David as “The Girl”. Isn’t it interesting, I asked, that you never actually learn what her “lovely and unusual” moniker is, while the novel is dominated and even named after the spectre of her predecessor? She huffed audibly in response.

Then there’s the fact that The Girl is 21, her beau Maxim twice that. ”AGE GAP!” Daughter shrieks with the kind of antipathy I reserve for Fowles. Apparently, it’s “disgusting” and not something her generation would tolerate (she has asked her mates and they all agree).

In vain did I point out that the pair were legally consenting adults, and that after a certain point, people are just people rather than birth dates. Yes, two decades is a lot and yes, people generally find more in common among those of their own age, but I can name several friends who found love in May-to-December relationships.

We have pushed on with the promise of more action to come, but I’m not confident Rebecca will last the course. It’s a bit slow, and even in its chasteness, still rather adult in its themes of loneliness and social mobility. Perhaps I should’ve started with Jamaica Inn, which is more of a romp, and with a location you can visit to boot.

I don’t want our cosy bedtime chats to come to an abrupt end thanks to an unpopular choice on my part, so with apologies to Daphne, I’ll keep the Famous Five under my pillow just in case.

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.