Compiled by Judith Field

Imagine yourself walking through Truro 250 years ago. The King was George III, the USA was a British colony, and it was the Age of Enlightenment. Music, science and free-thinking flourished – an exciting era brought to life by Winston Graham in Poldark.

Looking at the city, you would have felt a surge of pride. The tin and copper trades meant that Georgian Truro was booming, the social and business centre of Cornwall. Leading families like the Lemons, Boscawens and Daniells left their mark not only in the history books, but in the names of the streets of the city.

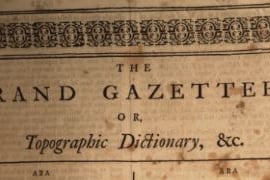

As Andrew Brice recorded in ‘The Great Gazetteer’ in 1759: “Here are very good provisions… and People of Fashion as elegantly dressed and served up as other wheres. The Gentry are moreover famed for politeness and hospitality.

“In very deed (and all joking thrown aside),” he continued, “some modern houses here, within as well as without, would not ill-become the best Square of London or of Westminster; nor might some of the Best Inhabitants disgrace a Drawing Room.”

Yet Brice had noted one defect - something that needed to be corrected if the town was truly to aspire to Georgian fashionability: the church. It had a “good old Gothish edifice” but “wants a handsome Tower, the pitiful little Thing which contains the single Bell looking rather like a Pidgeon-Hut than a Church Tower or Steeple.”

Truro owed its existence to the ability to cross by foot the rivers that run to the sea at Falmouth. Sandwiched between the Kenwyn and the Allen was the old Tudor church of St Mary. Recently, however, the ‘Evangelical Awakening’ led by John and Charles Wesley had created a new focus on preaching rather than ritual.

Georgian Truro needed a place of worship in keeping with the spirit of the age – a fine church with pews, a spire, big windows letting in natural light and, very importantly, a prominent pulpit.

St Mary’s Church was re-modelled in the mid-1700s, adding a spire in 1768. As with all ‘improvements’, there was a downside as well as an upside. Letting in the light had meant destroying almost all the medieval stained glass, for instance.

And while pews could be let out to generate money to support the church, disputes arose about who got to sit in the best seats - or be buried under them. The Rector, Charles Pye, had to take a decision in 1777 that no one could be buried inside the church for less than £5, as so many of the seats had been damaged by digging!

St Mary’s Parish Church is now the oldest part of Truro Cathedral, known as St Mary’s Aisle. The top of its 1768 steeple can still be seen on the cathedral green, and the aisle itself, with its beautiful light interior and pulpit, will re-open in June after extensive roof repairs.

To offer your support, simply search online for ‘Parish Giving Scheme Truro Cathedral’ or become a Friend at www.friendsoftrurocathedral.org.uk

Comments

This article has no comments yet. Be the first to leave a comment.